Elise Sormani is French and has lived in Cape Town (South Africa) for ten years, where she works on sustainable transition and the alignment of the economy with natural ecosystems, justice and social equity. After starting out in marketing in Europe, she turned to sustainable development. Her career has evolved around corporate social responsibility (CSR) and the circular economy, through various roles in the public sector, recycling, ethical fashion and as an independent consultant. Elise is also the mother of two daughters and has a passion for pilates, dance, nature, good wine, laughter and literature. Her move to South Africa was motivated by a professional opportunity for her husband, a change that was initially unexpected for Elise, who was considering living in Latin America, but which became a gradual infatuation with the region, despite the country’s historical challenges.

How did you become interested in ethical fashion?

When I arrived in South Africa, I had to reinvent my career. I took a sewing course, and from there was born the idea of creating an ethical company that would give work to women in the slums and produce bags that make sense and bring real value to society. So it was with this in mind that I launched WeAllShareRoots in 2016. Over the years, we have added materials issues to our social impact. I was the first brand in Africa to use Piñatex and I printed my own materials with vegetable-based ink. As far as communication is concerned, I’ve also refused to promote commercial holidays such as Valentine’s Day. I refuse to advertise on social networks, because of the controversial use of personal data. Finally, I chose to explore the circularity of materials and the reuse of waste. In fact, I’ve designed product lines using only scraps, and I’ve collaborated extensively with other brands to bring their own surplus fabrics to life.

I’m also familiar with the other side of the coin: a market in demand but reluctant to pay more for ethical products, the lack of suppliers of truly sustainable materials, especially in Africa, the cash-flow headaches of any entrepreneur, etc.

In 2019, faced with the impact of COVID on my business, I decided to deepen my knowledge of responsible business practices. I was able to discover the extent of the problems associated with the fashion industry, such as plastic pollution, overproduction and end-of-life issues.

Regarding the latest report on African fashion for UNESCO (2023), to which you contributed: what do you know about cotton fields?

As far as cotton fields are concerned, it’s interesting to reconnect the fashion and textile industry with nature, the fields and the farmers. We tend to forget that this is where the industry begins. Cotton yarns are not born in factories by industrial miracle! The story begins in the fields. And in Africa, it’s this step in particular that makes the fashion and textiles sector the second largest employer on the continent. Cotton is the main natural fiber in Africa: 37 of the 54 African countries produce cotton. It is also a crucial source of income for many small local farmers.

Unfortunately, the vast majority of cotton produced is exported abroad to be spun and processed into textiles. This is where most of the value is created.

“It is fundamental for Africa to industrialize and keep more of the value chain on its territory, creating GDP, a positive trade balance and jobs.”

Elise Sormani

What’s more, to produce clothing, Africa has to re-import the cotton once it has been processed. This means additional costs and penalties for local designers.

On a more positive note, Africa has the potential to become a leader in sustainable cotton growing: organic cotton fiber production in sub-Saharan Africa is set to increase by more than 90 percent between 2019 and 2020. This could open up significant development potential, as well as helping to alleviate the rather heavy environmental burden of current cotton cultivation.

What about the mountains of textile waste imported from the West…?

This is a complicated subject. On the one hand, it’s absolutely unacceptable that so-called “developed” countries should be able to export their waste to other countries, without being able to treat it locally. Africa is clearly not the dustbin of the world.

Under the guise of donations and good works, Europe and the USA export 150 to 200 tonnes of textiles a day to Africa, according to Greenpeace figures.

“40 percent of these textiles are not reusable, so they end up polluting open-air landfills on the continent.”

A pollution that Africa could do without, already plagued by the headache of dealing with its own waste. What’s more, this traffic feeds a veritable mafia network and offers direct competition, difficult to combat, for local brands and designers.

But on the other hand, the continent, especially Ghana, has become dependent on these imports. Not only do they feed a whole informal sector that has grown up around them, but they are also a source of clothing for many locals who don’t have the means to access brands and labels, which are often international. Employment and development opportunities have also been created with numerous local tailors and dressmakers who revisit and readjust second-hand garments, as well as industrial recycling pilots and NGOs very active locally in upcycling and social reintegration.

In fact, every time an African country decides to ban imports of used clothing, many voices are raised to congratulate them and to express concern for the future of a whole section of the local population.

…young designers…?

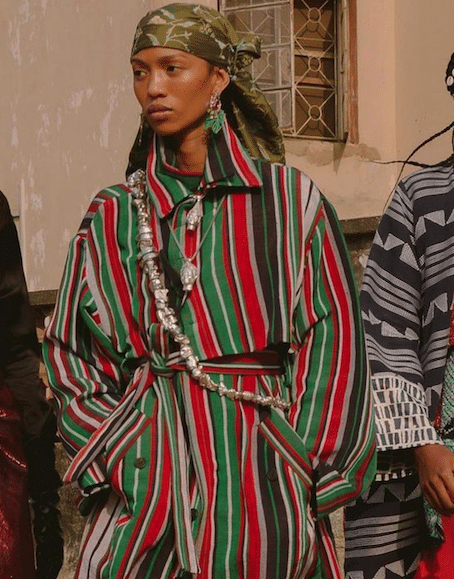

Africa is a particularly young and creative continent. It’s teeming with young talents who interpret modern and traditional codes in their own way. With the emergence of ” made in Africa ” consumption, both locally and internationally, via the diaspora in particular, many young talents have the wind in their sails and are enjoying great visibility. But, as we’ll see later, the obstacles to real development of the fashion sector in Africa are many, and many are still in the shadows.

In all cases, it’s particularly interesting to see young designers showcasing the techniques and fabrics of their countries, while giving them a contemporary twist. The notion of identity is very strong locally.

…and the luxury goods industry?

Africa is home to many emblematic haute couture brands and designers: Alphadi, Christie Brown, Imane Ayissi, Thebe Magugu, Kenneth Ize and others. With a strong presence on the international scene, they also cater to the needs and desires of a growing segment of Africa’s population: the wealthy. The Africa Wealth Report 2023 forecasts a 42% increase in the number of African millionaires over the next 10 years.

As theUnesco reportthe impact of the work of luxury designers extends far beyond their products: they are true agents of change and drivers of innovation, operating at the crucial juncture between craft, art and industry. They support a whole local ecosystem through their brands: textile craftsmen, seamstresses, assemblers, models and more. They play an active role on the continent in the development of a recognized and appreciated industry, but also internationally through their visibility and desirability.

Local fashion weeks are on the rise, starting with Lagos Fashion Week in Nigeria, now recognized worldwide, and SA Fashion Week in South Africa.

We’re also seeing a lot of links being forged “in the other direction”, with international brands exploring local creativity, as was the case not long ago with Chanel and its first sub-Saharan fashion show, which was also accompanied by beautiful collaborations with local artisans.

What barriers do you think Africa faces in developing its full potential?

Africa faces many barriers to the development of its fashion industry, despite its international potential. The Unesco report identifies five main structural obstacles: lack of coherence and coordination in support policies, insufficient protection of intellectual property rights for traditional textiles, shortcomings in education and training in the fashion trades, lack of investment and infrastructure, and negative environmental impacts.

These problems are compounded by other difficulties such as the high cost of textiles, the lack of skills in the modern textile industry, shopping habits geared towards fast fashion, the presence of second-hand clothing, and the lack of logistical development for export. These obstacles stand in the way of the creation of a strong and sustainable African fashion industry.

Sustainability: why is Africa a source of inspiration?

Without a shadow of a doubt, if there’s one continent that could lead the way in the art of ” doing more with less “, it’s Africa. There’s a real local tradition of recycling, upcycling and repairing. Materials and products are used and reused to the maximum by the vast majority of the population. The circular economy comes into its own here, especially in the informal sector.

As far as the fashion and textile industry is concerned, there are many indigenous natural fibers (raffia, jute, bamboo, linen, hemp, coir, sisal, etc.) whose extraction and weaving techniques are traditional and often done by hand. And many of these practices, along with those of weaving, vegetable dyeing and ornamenting, are thousands of years old and give rise to a large number of unique, handmade, high-quality textiles – the very definition of today’s famous “slow fashion”. The social impact of this work is also considerable. Traditional fabrics not only preserve ancient skills, but also often pay dividends to marginalized communities. By giving preference to local artisans and producers, brands and designers support an ecosystem that creates local resources and jobs.

But ” made in Africa ” doesn’t necessarily mean sustainable. As everywhere else in the world, the transparency of manufacturing processes still leaves a lot to be desired, and it’s not always clear exactly how and where clothes are made. It’s also important to distinguish between “designed and assembled” in Africa and “produced in Africa from A to Z”. As is often the case with European products, fabrics may have been sourced in Asia, to the detriment or even peril of local textiles.

What do you think of fast-fashion brands like H&M, which are implementing new initiatives to reduce their impact?

Personally, I have mixed feelings about a brand like H&M. On the one hand, its business model, based on what is known as Fast Fashion (high volume, low costs, in short), is absolutely incompatible with the notion of responsible fashion. A huge part of fashion’s impact is due to overproduction and overconsumption.

“So, no matter how much we change polyester for organic cotton, we’ll still continue to take up too many natural resources and produce too much waste. So there’s a real basic contradiction.”

Nevertheless, at the same time, few brands offer “sustainable fashion” at low prices and have such access to such a large number of consumers. They therefore contribute to a certain democratization of these concepts, such as access to more responsible materials, recycling of clothes at the end of their life, and so on. Once again, this is just the tip of the iceberg, but the transition must be everyone’s concern, and the advantage of these huge brands is also their reach and visibility.

Unfortunately, this blurred positioning of responsible fast fashion (which is an oxymoron!) also has repercussions on H&M’s financial results, threatened by the emergence of players for whom social and environmental issues are not a real concern, such as Shein or Temu, and who are therefore much more competitive in terms of price, costs and design. That’s a shame.

What do you think of France’s bill to impose a penalty/reward system on the price of fast fashion?

I fully support this initiative, because as long as fast-fashion brands remain so inexpensive and therefore so attractive to consumers (price still remains one of the number-one criteria for choice), we’ll never be able to combat overproduction, human exploitation, cheap and highly polluting production methods, low garment quality and abundant waste.

Nonetheless, I agree with the associations calling for the marketing criterion to be lowered from 1,000 new products per day to 5,000 new models per year. This would allow the inclusion of many fast-fashion brands, which are just as harmful to the environment as those initially targeted by the bill.

Do you have any new projects for this year?

I’m in contact with the organizers of South Africa’s leading textile trade event to help them integrate more responsible content and awareness-raising.

I’m also working closely with a local organization that aims to launch major circular fashion events in Africa this year, notably in Kenya and South Africa.

And as always, I like to use my freedom of tone and spirit to share the innovations and contradictions of ethical fashion on Linkedin.

Finally, I’m keeping my hat on as coordinator of a volunteer group in France, the Collectif Démarquéwhich works to raise awareness of sustainable fashion issues and the impact of conventional fashion on Instagram and among young audiences.

And, as a big novelty, I’m also preparing for my family’s return to France in the next few months – a big personal and professional challenge after a decade in Africa!

Photo One: Pexels / Clint Maliq